Projects

Scroll down or click the project titles for more

Edible Estates

Fritz Haeg

Biotechnology Campaign

Beehive Design Collective

As Above, So Below

Nance Klehm

Temescal Amity Works: Big Backyard

Ted Purves & Susanne Cockrell

Molecular Invasion

Critical

Art Ensemble & Beatriz Da Costa & Claire Pentecost

Chew on This

The Center for Urban Pedagogy with

Amanda Matles

Moisture

Deena Capparelli & Moisture

Santa Ana River Trail Native Food Project

Lisa Tucker

Organic Industry Structure

Philip H. Howard

Shepherding Sovereignty

Amy Franceschini

Edible Estates

Fritz Haeg

www.fritzhaeg.com

The Edible Estates project proposes the replacement of the domestic front lawn with a highly productive edible landscape. It was initiated by architect and artist Fritz Haeg on Independence Day, 2005, with the planting of the first regional prototype garden in the geographic center of the United States, Salina, Kansas. Since then five more prototype gardens have been created, in Lakewood, California; Maplewood, New Jersey; London, England; Austin, Texas and Baltimore, Maryland, and will ultimately be established in nine cities across the United States.

Edible Estates: Attack on the Front Lawn documents the first four gardens with firsthand accounts written by the owners, garden plans, and photographs illustrating the creation of the gardens, from ripping up the grass to harvesting a wide variety of fruits, vegetables, and herbs. Essays by landscape architect Diana Balmori, garden and food writer Rosalind Creasy, Fritz Haeg, author Michael Pollan, and artist and writer Lesley Stern set the Edible Estates project in the context of larger issues concerning the environment, global food production, and generating a sense of community in our urban and suburban neighborhoods. The book also includes reports and photographs from the owners of other edible front yards around the country, and some helpful resources to guide you in making your own Edible Estate.

top

Graphic Campaign Banners

Beehive Design Collective

www.beehivecollective.org

The Biojustice, Biodevastation and Puppeteer posters were the first of the Beehive Collective's graphic work, created in the Spring of 2000, as outreach posters for the 4th Biodevastation conference in Boston, a gathering of the grassroots against the BIO industry Annual Meeting. For more information about this yearly event visit www.biodev.org

top

As Above, So Below

Nance Klehm

www.spontaneousvegetation.net

Weeds have followed the plow. They are artifacts of our modern food culture, Agriculture. The way we eat and live by ripping and removing the living soil of the indigenous deep rooted-structure of tall grasses, trees and shrubs exposes soil to wayward seeds. The most assertive weedy seeds settle themselves into these open patches of soil and establish themselves. When the Mayflower arrived in 1620, there were no dandelions in North America. By 1671, they were everywhere.

Weeds adapt the condition at hand, make use of marginalized soils that agricultural plants can’t. They optimize vitamins and mineral contents within their bodies, create passageways through the soil for water and air to flow via their deep roots and create forage for animals and insects. Preventing further degradation of soils by covering the land’s tilled surface, they prepare and heal the soil for other plants. Weeds enhance our internal and external landscapes’ capacity to support and heal themselves. Weeds are our reward for not going native.

top

Temescal Amity Works: Big Backyard

Ted Purves, Susanne Cockrell

www.fieldfaring.org

Temescal Amity Works was a multi-year project (July 2004-January 2007) sited in the Temescal neighborhood of Oakland, California. We have lived in the neighborhood since 1999, and when we conceived of the project, we saw it as a way to localize our attention and to restructure our practice to work in a community that we were not external to. We considered the project to be a social sculpture that also drew upon historical models of mutual-aid societies, barn-raisings, DIY collectives and urban communism. We were (and still are) interested in how a specific community built relationships through personal and casual economies. To accomplish this, we created two interlocking programs, The Big Back Yard and Reading Room.

The Big Back Yard built on the history of the neighborhood as an Italian-American, immigrant community that was planted with citrus and fruit trees. Today, these trees still bear fruit while the culture that planted them has dwindled. Much of the harvest rots on the ground or is hauled away by the city. The Big Backyard was based around a hand-built, steel pushcart that we made to collect surplus fruits and vegetables from neighborhood yards, which we gave away fresh or re-distributed in the forms of collective marmalades and fruit butters.The Reading Room, located at a storefront space just off Telegraph Avenue, contextualized the ongoing experience of the Big Backyard through casual contact during open hours, as well as through a series of public events, film screenings and a small resource library. We also invited local artists, historians and others to create projects that overlaid themselves onto Temescal Amity Works in a productive and complicated way, making available our space and resources, including modest re-distributions of our funding. These collaborations included a Yellow Car Parade, a seed-exchange board, a marathon bread-baking workshop and a Broom Mending walk.

Over the course of the project, our storefront was open most weekends. We harvested and redistributed thousands of free oranges, lemons, apples, and other produce from local yards. We made and gave away many jars of marmalade, fig conserve and apple butter. We published a series of postcards documenting local groups and collectives, venerable fruit trees, and the local landscape. We also produced a neighborhood resource map that was given out to all of the residents of the neighborhood and continues to be distributed through local businesses.

While the project could have continued indefinitely, in January of 2007, we decided to close the storefront. We had observed that the longer the storefront remained in operation, the projects identity as a service became more ingrained in the neighborhood’s “consciousness”; which worked against our own interest in jump-starting a network, wherein residents would begin to circulate their backyard surplus amongst themselves. The tension between these two endpoints became clearer during a final discussion with neighbors that we hosted in the space on the closing weekend. While many who attended felt that the dialogue and concepts generated through the storefront and programs had been of real interest to the neighborhood, there were also residents who felt that the project didn’t fully create a harvesting service for the neighborhood on a scale large enough to address issues of food justice and community health. While this was not really part of our intent or interest, such feelings highlighted some core issues about practicing as artists in a community context; what makes for a successful art project can often seriously diverge from the expectations placed on activist and non-profit services, and this divergence can be heightened when the art project borrows some of its outward form from such organizations.

This past summer we have come across two separate projects in our neighborhood that involve foraging and crop sharing. One called Forage Oakland and the other is called Pueblo Project which is funded by

We are currently working on a follow up project with the neighborhood, building on our growing interest in the creation of means and models rather than services. This project, called Green Language: Tools for Urban Foraging in the Temescal Neighborhood will continue to focus awareness on neighborhood micro-economies, sustainable living, cooperative social networks and local history through the insertion of free harvesting tools into the local tool-lending library, linked with after-school curricula in the neighborhood primary schools. These tools and their use will be publicized through a series of free illustrated pamphlets that will be distributed through the neighborhood newssheet and will form the basic curriculum for the school program. In this project, we are collaborating with two other neighborhood residents (one is an artist and chef and the other is a nutritional and environmental educator) who we met through Temescal Amity Works. One of the ideas behind this phase is to work directly through pre-existing organizations, rather than through “creating” a new one. The intent is to continue to craft an ongoing consciousness around the “big backyard” and its potential within a local casual economy.

top

Molecular Invasion

Critical Art Ensemble & Beatriz Da Costa & Claire Pentecost

www.critical-art.net

Documentation of CAE’s Molecular Invasion project (Corcoran 2002) with additional resources.

From Original project press release for Corcoran performance 2002 –

Washington DC - Corcoran College of Art + Design’s Visiting Artists Program presents Molecular Invasion, a new experimental exhibition by the artist/activist collective Critical Art Ensemble (CAE) and Beatriz da Costa with Botanical Consultant Claire Pentecost beginning October 25. For the past five years CAE’s work has focused on biotechnology and the new forms of representation that continue to emerge from this vast field. As tactical media artists, the group has completed major projects examining various aspects of the biotech revolution in theatrical form that invite public participation. The Corcoran exhibition includes two related parts. The first part includes photodocumentation, CD-ROMs, and ephemera from previous CAE projects. The second part, Molecular Invasion, is a live public experiment in the gallery where the collective will attempt to reverse engineer genetically modified cash crops.

CAE’s previous biotech projects help to provide a context for their live experiment at the Corcoran. For example, the large-scale performance Flesh Machine (1997-98), which highlighted eugenics in the discourse and practice of current human reproduction technologies, featured the actual genetic screening of audience members and the diary of a couple going through in-vitro fertilization. The performance Society for Reproductive Anachronisms (1999) engaged the audience in dialogue about the danger of medical intervention in reproduction. In Cult of the New Eve (2000), CAE used the apocalyptic language of an imaginary cult to explore rhetoric surrounding recent genomic developments. For all of their projects, CAE enlists the aid of scientific specialists in the given fields under scrutiny. Often, they situate functioning labs on-site to bring people into contact with processes they would otherwise never come into contact with. All of this has the effect of demystifying the scientific process and contributing to an informed, critical discourse on biotechnology.

For the Molecular Invasion project, CAE will grow Monsanto RoundUp Ready cash crops (canola, soy, and corn) in experimental and control groups in the gallery for the duration of the exhibition. According to CAE, RoundUp ready crops have already become a super-pest in North America and they continually threaten to contaminate agricultural biodiversity around the world as their sales and distribution increases. CAE’s project provides a model for amateur molecular intervention through the application of a simple pyridoxal compound on the experimental group of plants. If successful, the compound will essentially reverse engineer the genetic modifications made to the plants, thereby making them vulnerable to the crippling effects of RoundUp herbicide. CAE will also produce a CD-ROM and other materials that explain the Molecular Invasion project in detail with the goal of raising public awareness of the dangers and implications of the production and deployment of transgenic crops. Students from the Corcoran’s Bachelor of Fine Arts program will assist the artists at every stage of the project and will hold performative hours during the exhibition in order to maintain the experiment and dialogue with the public. This project is partially funded by Creative Capital.

top

Chew on This

Center for Urban Pedagogy with Amanda Matles

www.anothercupdevelopment.org

Where in the world does our food come from? How does its journey to our plate effect the environment and our quality of life? These questions were the point of departure forChew On This, an investigation into the global flows of food by CUP teaching artist Amanda Matles with high school students of four environmental science classes at the Heritage School in East Harlem, New York, in spring 2006.

Chew On This tested our very notion of what food is and where it comes from. Each class picked their top three favorite foods to use as the basis of our investigation. At first, eating seemed simple, but the picture soon became more complex as the students traced the ingredients in their pizza, pasta, cheesecake, chicken, lo mien, and watermelon back to farmland and fields in places as far away as China and Australia and as close as rural New Jersey.

Students worked to calculate the fuel resources required to bring their favorite foods to East Harlem, and we found that calculating 'food miles' is actually very complicated and involves many people in an intricate chain of food distribution. The students interviewed farmers at a local farmers market about what it takes to grow and distribute food locally and discussed local versus long distance eating.

A blind taste test with organic and conventional foods grown around the world was conducted in the classroom. We went on a foraging expedition in Central Park to learn about edible plants that grow on our streets and in our parks. With all this information, the students produced a large scale poster to introduce others to the edible environment and a zine containing recipes using ingredients that can be found growing on the street and in the city.

top

Moisture - Deena Capparelli & Moisture

http://moisture.greenmuseum.org

Moisture is an experimental research project undertaken by a Los Angeles-based artist collective. Focused on developing location-sensitive structures for the collection, retention, and use/re-use of water in the Mojave Desert, the collective are invested in creating micro-climates within one of the driest desert regions on the planet. Since the winter of 2002, the evolving project has developed into an annual research program centered on Harper Dry Lake, near Hinkley, California. The current phase of the program involves the design and construction of functional sculptural objects, installed in relation to the ground, and the hydraulic matrix of the region. All individual components of Moisture are to be seen as puzzle-pieces aiding in the long-range understanding of this unique closed-basin. The Harper Basin is a distinct drainage basin within the Mojave Desert, and as an exhausted agricultural area, with a large dry lake at its bottom, its history and present condition is emblematic of modern human development in desert regions. The Moisture collective intend to establish a prolonged presence in this Harper Basin, working both with and against the regions changing water cycles.

top

Santa Ana River Trail Native Food Project

Lisa Tucker

http://sartfood.blogspot.com

Biking to work along the Santa Ana River Trail has given me time to consider some of its quirks. The entrance I take is on Waterman Avenue in San Bernardino, with a path that winds around the 215 and 10 freeways and along a rather barren, sandy bed with little vegetation. What I find amusing are the concrete tables and benches for picnickers, where I have yet to see anyone sit because the climate is so hot, dry, and windy. In fact, the whole trail feels like the arid desert Southern California is, with an occasional stream of water appearing, and then disappearing into the rocks. None of the benches are near the few trees along the path– just miles and miles of sandy, predominantly plant-free soil– uninviting furnishings within an inhospitable terrain.

Other inhabitants, or just plain “the other”

The homeless who live in or near the Riverbed are another curious presence. They usually clear out by 6 or 7 o’clock a.m., but periodically I ride early enough to meet some of them. One morning on the way to work, I was reminded of the homeless folk who attend art openings at the gallery and museum where I work in Downtown Riverside. Since security officers have been hired for receptions, I haven’t seen as many of the downtrodden, but when they come there are a few who line their pockets with cubes of cheese and other buffet fare. Why would someone who gets free food from community services want squares of cheddar? There are two reasons, assures my husband who is a social worker. First is the thrill of taking something that is not yours, or in this case taking more than is socially acceptable. The other is variety. I pondered the luxury of food diversity. I never want to see edamame again after buying an industrial size box from Costco three years ago. I’d imagine it’s the same for those who rely on soup kitchens, though doubtful it’s edamame they despise. Riverside and San Bernardino County food banks and soup kitchens don’t have the resources to keep large quantities of refrigerated goods stocked, which means less fresh milk products, fruits and vegetables. Food found on the shelves is most likely processed, dry packed or canned, according to Catherine Mailliard, director of family outreach at the Community Food Pantry. At present it’s been hard for local pantries to keep up with demand for even the non-perishable items. Donations are down and as the following chart indicates, the number of residents receiving food stamps in San Bernardino and Riverside counties rose considerably this year. Food stamps are rarely adequate and many recipients rely on the generosity of other organizations in addition to what is provided by the county.

Riverside County Food Stamp Recipients

May 2007 31,017

May 2008 40,590

San Bernardino County Food Stamp Recipients

May 2007 46,123

May 2008 57,962

Source: Riverside County Department of Public Social Services and San Bernardino Transitional Assistance Department

Proposal

Contemplating the empty picnic tables, rarity of vegetation along the bike path, and need of novel fresh food, I devised a plan. Why not plant gardens of native edibles and trees along the trail? I enjoy plant propagation and could easily harvest seeds, take cuttings and transplant existing California flora. Even more interesting to me is the notion of a guerilla garden, enlisting the help of cyclists and those who live along the river.

top

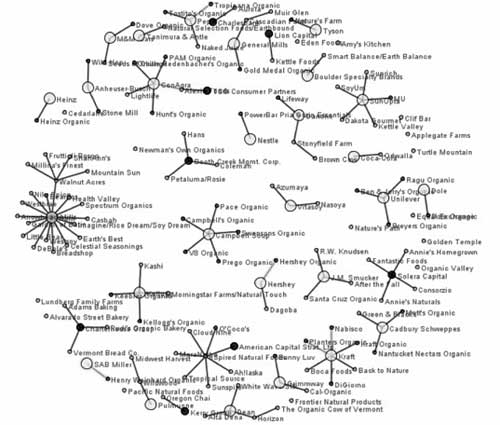

Organic Industry Structure

Philip H. Howard

www.msu.edu/~howardp

"Organic" has undergone a transformation from a movement to a $20 billion a year industry in the United States. This project explores the changes in ownership and control that have accompanied the implementation of a federal organic standard. This transition began in the mid-1990s, as US Department of Agriculture moved to replace an existing "patchwork" of differing state/regional standards. Some of these changes are well-hidden, as few companies that have acquired organic brands make these ownership ties apparent on product labels. The overall trend, however, is increasing industry domination by large, transnational corporations.

top

Shepherding Sovereignty

Amy Franceschini

www.futurefarmers.com

“The current industrialized agribusiness model has been deliberately planned for the complete vertical integration and to dominate all agriculture activities. This model exploits workers and concentrates economic and political power. We need a decentralized model where production, processing, distribution and consumption are controlled by the people the communities themselves and not by transnational corporations.”

-La Via Campesina (1)

In September 2007 a flood of sheep and shepherds from 32 countries traversed the city of Madrid. Before entering the city, the sheep gathered in a public park on the outskirts of town to fuel up for the trek across an ancient grazing route now threatened by urban sprawl and man-made frontiers. The World Congress of Nomadic and Transhumant Pastoralists hosting herdsmen from the Masai plains of Kenya and the steppes of Mongolia has now re-established the right of shepherds to drive their herds through the capital of Spain’s empire. Instigated by artist and organizer Fernando Garcia Dory in 2003, the gathering has become instrumental in mobilizing people and organizations nationally like Platforma Rural, an alliance of stakeholders including farmers unions, consumers’ associations, development NGOs, environmental organisations, and workers’ unions (industry or agriculture) and internationally the European Platform for Food Sovereignty, La Via Campesina [the International Peasant Movement] and others. This gathering lead Dory to initiate a shepherd’s summer school in an attempt to revive an age-old human occupation, which embodies the complex symbiotic relationship between humans and animals in a natural state. Within a decade the school has become highly oversubscribed, as people everywhere come seeking an alternative to the extremes of the European lowland climate, and the chance to spend several months a year in the enriching presence of goats and sheep on the mountain ranges of Europe. The Congress itself developed into a forum for the exchange of traditional knowledge of all kinds and skills such as horse-archery and soda bread baking.

This gathering in Spain is an example of the actualization of another possible mode of operating – a collective being of wonder (2) –a primary experience that goes beyond the imagined and makes visible a collective resistance (a moment of solidarity– a sovereign space) to a particular current that controls the way we move through our lives.

While the re-establishment of the ancient tradition of shepherding is in effect in Spain, to the east an ancient tradition of seed saving seems to be strategically being destroyed. Following the U.S. occupation in Iraq in 2003, the National seedbank in Abu Graib was destroyed and looted. Under the veil of humanitarian aid and reconstruction, a Frankenstein effect seems to be unfolding in the Fertile Crescent–where humans began to control the growth of grain in 8000 b.c., (the birth of agriculture) today, 465 metric tons of wheat are being delivered to eastern Baghdad farmers as building blocks for a new economy. In September of 2003, Daniel Amstutz, U.S. senior ministry advisor for agriculture, was positioned in Iraq to lead reconstruction efforts. Amstutz was also CEO of Investor Services at Cargill, where he began in grain trading eventually heading the wheat desk and ending up at Goldman Sachs in grain futures trading. In early 2005, a newsletter of Garst Syngenta reported of donations of trademarked seed to Iraq, namely patented strains; 8380IT, 8288, 8285 and 8230IT. Under Paul Bremmer III, Administrator of a newly created Coalition Provisional Authority, 100 orders were put into effect intending to ‘help Iraq become a full member of the international trading system known as the World Trade Organization and to recognize the desirability of adopting modern intellectual property standards. Under order 81, of the hundred orders, ’Farmers are be prohibited from re-using seeds of protected varieties’.

1. La Via Campesina is an international movement which coordinates peasant organizations of small and middle-scale producers, agricultural workers, rural women, and indigenous communities from Asia, Africa, America, Europe. They are a coalition of over 100 organizations, advocating family-farm-based sustainable agriculture and were the group that first coined the term food sovereignty.

2. Rousseau, Jean-Jacques, Of the Social Contract, Book III, Chapter III.

In his 1762 treatise Of the Social Contract Rousseau argued, "the growth of the State giving the trustees of public authority more and means to abuse their power, the more the Government has to have force to contain the people, the more force the Sovereign should have in turn in order to contain the Government," with the understanding that the Sovereign is "a collective being of wonder" resulting from "the general will" of the people, and that "what any man, whoever he may be, orders on his own, is not a law” – and furthermore predicated on the assumption that the people have an unbiased means by which to ascertain the general will. Thus the legal maxim, "there is no law without a sovereign."

top